Tcache [UMDCTF 2024]

Tcache

Tcache (per-thread cache) was added in glibc 2.26 to make heap allocation more efficient by allowing each thread to have its own tcache.

Important things to know:

- Each thread has 64 singly-linked tcache bins (

TCACHE_MAX_BINS). - Each bin has a maximum of 7 chunks of the same size.

- A bin can have chunks ranging from 24 to 1032 bytes (on a 64-bit system).

- Each bin only has an

fdpointer. - Allocating from a tcache bin takes priority over every other bin.

- When

freeis called ormallocis invoked, this is the lifecycle (which bins will be used):- Initially checks tcache. If full or the size exceeds limits, looks in fastbins. If conditions are met, searches in unsorted bins, then small or large bins.

- For

malloconly, if no suitable bin is found, it tries obtaining memory from the top chunk. If that fails, it extends the heap. If both attempts fail, it returns null.

Tcache Structure

To understand better how the tcache works, I played a bit around with shellphishes GitHub project.

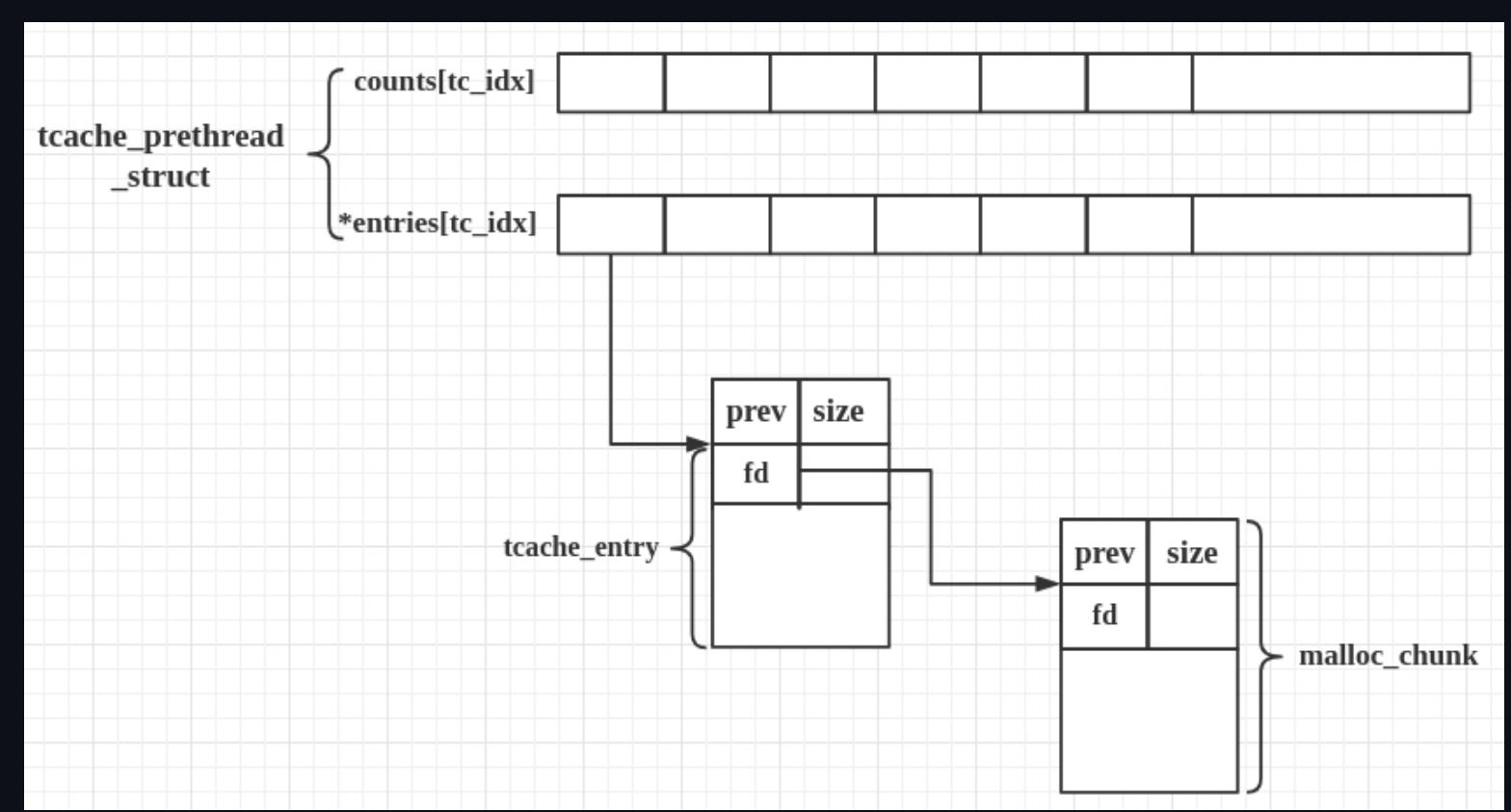

The tcache_entry structure is used to connect free chunks and has a pointer to the next free chunk of the same size (next points to the chunk’s user data, this is not the same as in fast bins).

The tcache_perthread_struct is meant to be a structure for each thread.

Tcache structure (libc 2.39, one of these per thread):

typedef struct tcache_entry

{

struct tcache_entry *next; // --> next_free chunk

uintptr_t key; // --> detect double frees added in glibc 2.29 (it points to the tcache_perthread_struct when freeing a chunk; it checks if the key is already set to point to the struct; if yes it most likely means it's a double free)

} tcache_entry;

/* There is one of these for each thread, which contains the

per-thread cache (hence "tcache_perthread_struct"). Keeping

overall size low is mildly important. Note that COUNTS and ENTRIES

are redundant (we could have just counted the linked list each

time), this is for performance reasons. */

typedef struct tcache_perthread_struct

{

uint16_t counts[TCACHE_MAX_BINS]; // --> count of free chunks for each size (max 7 of the same size) [define TCACHE_MAX_BINS 64]

tcache_entry *entries[TCACHE_MAX_BINS]; // --> points to the entry for each size

} tcache_perthread_struct;

The size of each type of bin is difiend as :

idx 0 bytes 0..24 (64-bit) or 0..12 (32-bit)

idx 1 bytes 25..40 or 13..20

idx 2 bytes 41..56 or 21..28

...

So when we malloc a new chunk it will take the last freed chunk.

Let’s see how __libc_malloc works with tcache:

- call MAYBE_INIT_TCACHE().

- If the tcache is empty, tcache_init() is invoked.

- Upon completion of step 2, it returns a tcache_perthread_struct.

- If the tcache entries are not empty, it will invoke tcache_get(), which retrieves the first chunk from the entries list and decrements the count. (

GETTING CHUNK)

tcache_get (size_t tc_idx)

{

tcache_entry *e = tcache->entries[tc_idx];

assert (tc_idx < TCACHE_MAX_BINS);

assert (tcache->entries[tc_idx] > 0);

tcache->entries[tc_idx] = e->next;

--(tcache->counts[tc_idx]); // Get a chunk, counts decreases

return (void *) e;

}

- When calling free(), it will call tcache_put() which adds the freed chunk. (

SETTING CHUNK)

/* Caller must ensure that we know tc_idx is valid and there's room

for more chunks. */

static __always_inline void

tcache_put (mchunkptr chunk, size_t tc_idx)

{

tcache_entry *e = (tcache_entry *) chunk2mem (chunk);

assert (tc_idx < TCACHE_MAX_BINS);

e->next = tcache->entries[tc_idx];

tcache->entries[tc_idx] = e;

++(tcache->counts[tc_idx]);

}

Typical exploit

Okay, now that we understand how the tcache works, let’s explore how we can exploit it, focusing on glibc 2.27.

For libc versions prior to 2.31:

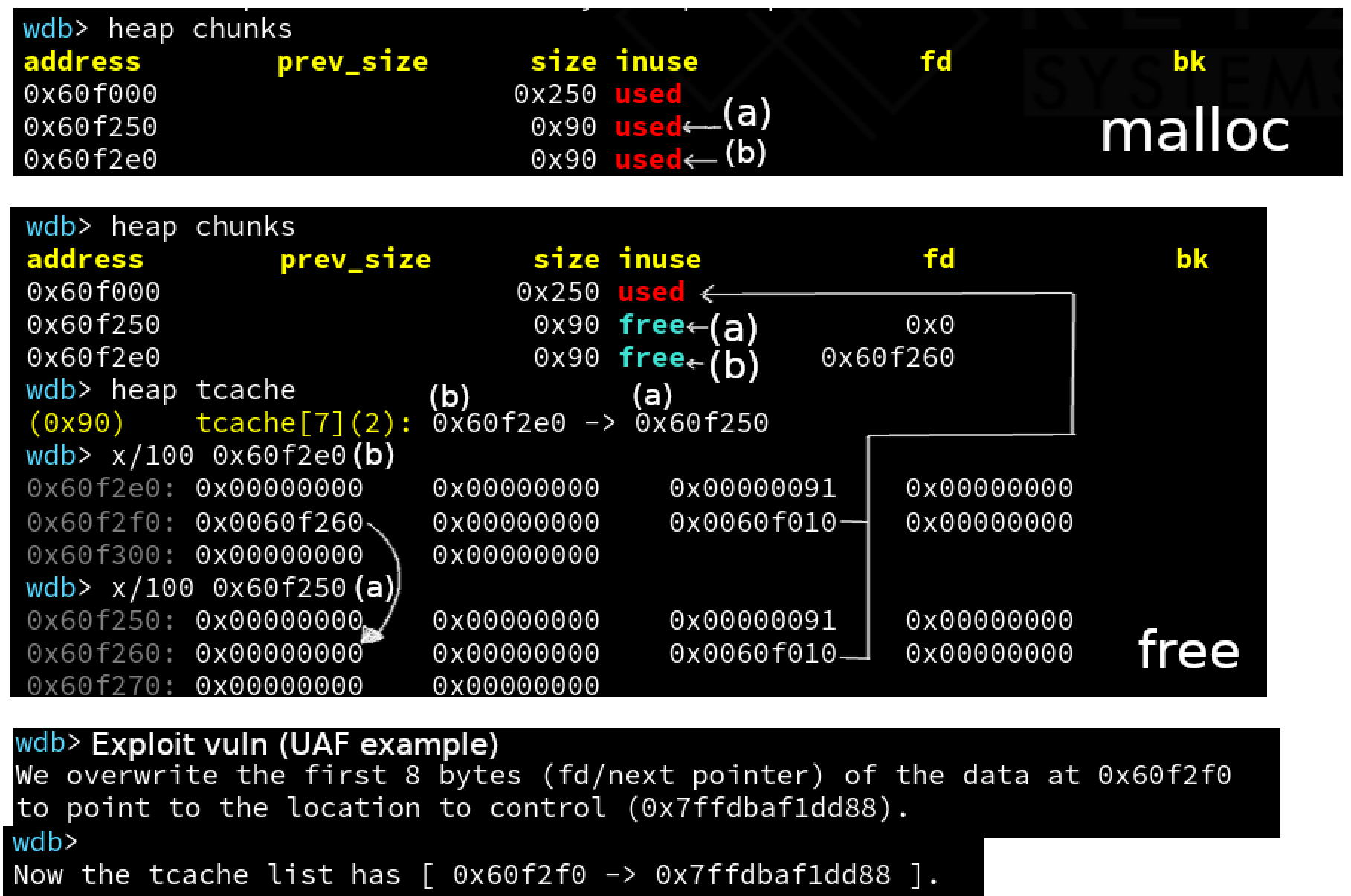

- Allocate two chunks.

- Free chunk ‘a’ and then chunk ‘b’.

- Tcache list: [address_bin_b -> address_bin_a] where bin_b has a forward pointer (fd) to address_bin_a.

- Overwrite (using a Use-After-Free, for example) the forward pointer (fd) of bin_b with a malicious address.

- Tcache list: [address_bin_b -> controlled_address]

- Call malloc.

- Tcache list: [controlled_address]

- Call malloc again to exploit the vulnerability, returning a pointer to an arbitrary location.

Memory layout (glibc 2.27):

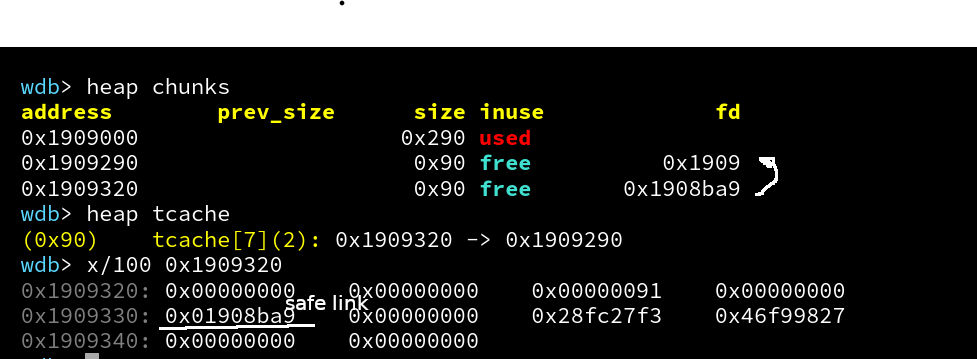

For other versions, the concept remains the same but may require adjustments. For instance, in glibc 2.32, the introduction of safe linking require additional considerations, such as a heap leak.

Memory layout (glibc 2.34):

I suggest experimenting a bit with the how2heap repository, it’s very cool!

Safe linking

Leaking from the heap isn’t that easy anymore, since glibc > 2.32 there is something called ‘safe linking’ (fastbins and tcachebins) which make heap exploits a little harder. Safe-linking’s goal is to prevent attackers from leaking heap addresses and arbitrarily overwriting linked-list metadata.

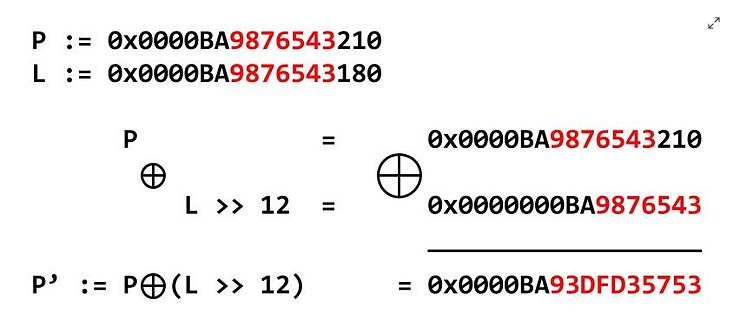

Safe linking implementation:

#define PROTECT_PTR(pos, ptr) \

((__typeof (ptr)) ((((size_t) pos) >> 12) ^ ((size_t) ptr)))

#define REVEAL_PTR(ptr) PROTECT_PTR (&ptr, ptr)

/*

pos - address of the fd field itself (L)

ptr - pointer value that would be held in the fd field of a free chunk (P)

>> 12 is to get rid of the predictable chunks of ASLR (last 3)

*/

Visual representation of the implementation:

Where P’ is what is stored in the heap chunk in the fd field, P is the fd pointer and L is the address of P. What we generally need is to leak P’ (heap leak) and have a ‘malicious’ address which we need to ’encrypt’ as in the formula so that the right value is inserted in the heap.

To get a more complete view of why this process isn’t a good protection method (in CTF’s), let’s see a nice example inpired from Galile0

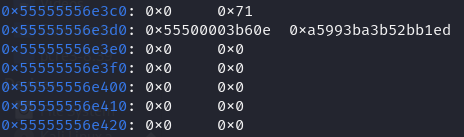

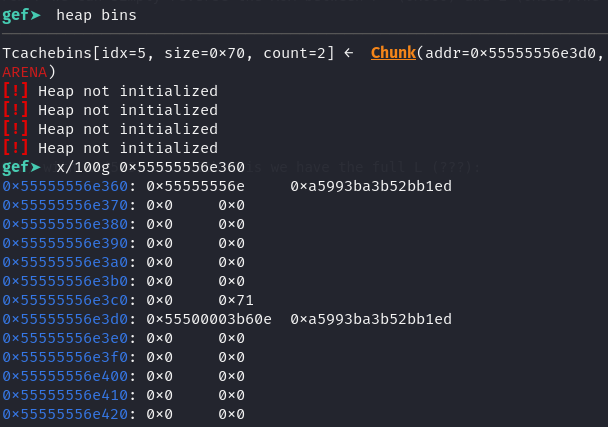

We have the following freed chunk:

Let’s say we have a heap leak and can retrieve the fd pointer: 0x000055500003b60e, now we can get all of the addresses by reversing the operations from the implementation.

P' = 0x000055500003b60e

L >> 12 = 0x0000000555XXX???

---------------------------------^

P = 0x0000555XXX???YYY

We know that the first three ’nibbles’ (0x555) are not randomized, so we begin with this information. Next, to determine the following ’nibbles’ from P, we can reverse the XOR between P’ (0x000) and L (0x555). Similarly, we can derive the ones for L (XXX):

P' = 0x000055500003b60e

L >> 12 = 0x0000000555555???

---------------------------------^

P = 0x0000555555???YYY

For the next nibble we repeat the process with P’ (0x03b) with L (555) and with this we have the full L (???):

P' = 0x000055500003b60e

L >> 12 = 0x000000055555556e

---------------------------------^

P = 0x000055555556eYYY

And now we can easily get the last ’nibble’:

P' = 0x000055500003b60e

L >> 12 = 0x000000055555556e

---------------------------------^

P = 0x000055555556e360

Let's check if P is indeed the fd pointer:

We can see that the we got the correct fd pointer. These are some functions that are generally used for this in CTF’s:

Deobfuscation function:

def deobfuscate(leak):

leak = 0xfff << 52

while leak:

v = val & leak

leak ^= (v >> 12)

leak >>= 12

return leak

An example function that obfuscates data for a payload:

def obfuscate(addr):

return (leak>>12) ^ addr